The Flashback malware family is among the first widespread malware on MacOS. Its story started in the fall of 2011. At first it went undetected for a couple of months, but then got a lot of attention in the spring of 2012 because it infected over 500,000 computers.

The first variants disguised themselves as an Adobe Flash player update. The attack usually started by directing the victim to a malicious website and using a pop-up to trick them into thinking that an Adobe Flash update is necessary. The malicious sample would then be downloaded and executed. After entering the user credentials, as requested during the installation, the victim allowed Flashback to self-install on their Mac.

Other variants used a Java-signed applet to deliver the malicious payload. By visiting a malicious website, the victim received a message from the Java interpreter requesting permission to run an applet that claimed to be signed by Apple. The certificate used in this case did not come from Apple; it was self-signed. As with the previous method, authorization allowed the delivery of the malicious payload. The method which was by far the most effective at propagating Flashback infection exploited two Java vulnerabilities: CVE-2012-0507 or CVE-2011-3544. In this case, the vulnerabilities enabled Flashback to automatically install without the user’s input or knowledge just by visiting a website containing the malicious Java applet, either directly or in an iframe. This approach infected more than half a million Macs. Over time, the methods of obfuscation of each component became more complex.

So, is Flashback still available and evolving in 2020? Adobe Flash has had a downtrend in usage for quite some time now. Even Adobe plans to stop supporting the Adobe Flash Media Player by the end of 2020. Interestingly, the ReversingLabs repository was enriched by more than 80 thousand different instances of Flashback malware in the past year. It is intriguing that this old threat, using almost completely deprecated disguises, is still so readily available in the wild.

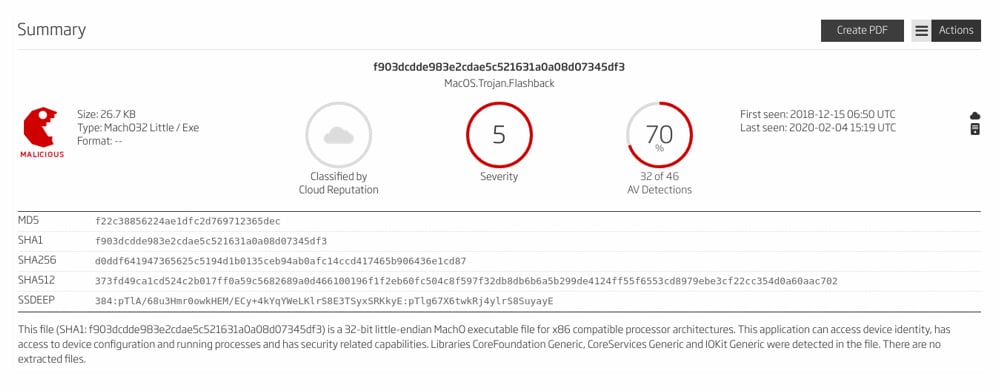

We decided to take a closer look at some of the newer Flashback samples, and analyze what happened and whether they evolved in any way. For this analysis, we used our Titanium Platform A1000 Malware Analysis and Hunting solution. The A1000 Malware Analysis Platform supports advanced hunting and investigation through the TitaniumCore high-speed automated static analysis engine. It is integrated with file reputation services to provide in-depth rich context and threat classification for over 10 billion files and across all supported file types.

First, we will make use of the TitaniumCloud integration and the Advanced Search feature on A1000 to search across 10 billion goodware and malware files, and find samples that are of the FlashBack malware family. With the search query threatname:Flashback, we can find interesting samples and retrieve them to the A1000 solution for more detailed analysis.

Figure 1: Searching for FlashBack samples

At first glance, the sample summary page doesn't show anything interesting. We can see the sample has high severity, 12 detections, and is classified as a malicious MacOS.Trojan.Flashback sample.

Figure 2: A1000 sample summary page

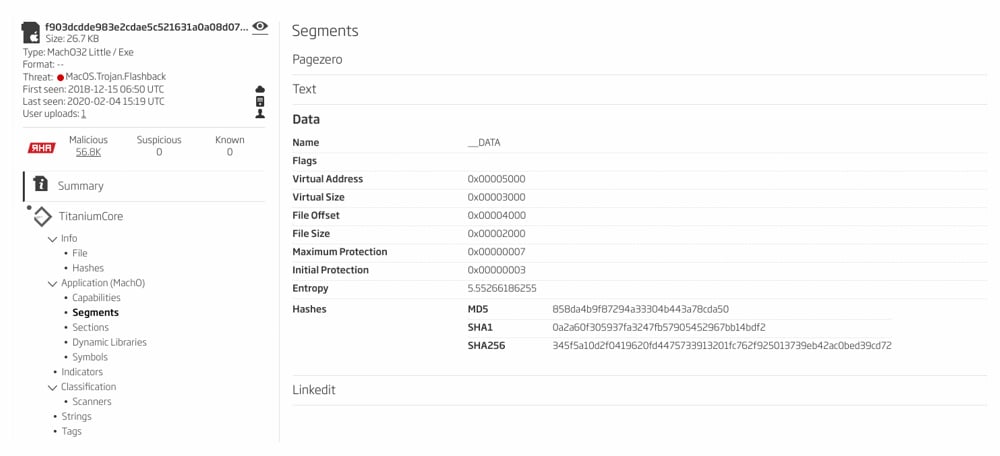

A closer look reveals that our cherry-picked sample set has the same SSDEEP hash, and the same RHA hash. While this is peculiar, it is not uncommon for some polymorphic malware families. Let’s start exploring the binary segments. The sample consists of four segments: Pagezero, Text, Data, and Linkedit. The first three segments have the same content and hashes, meaning that these files differ only by their Linkedit segment.

Figure 3: Sample segments research

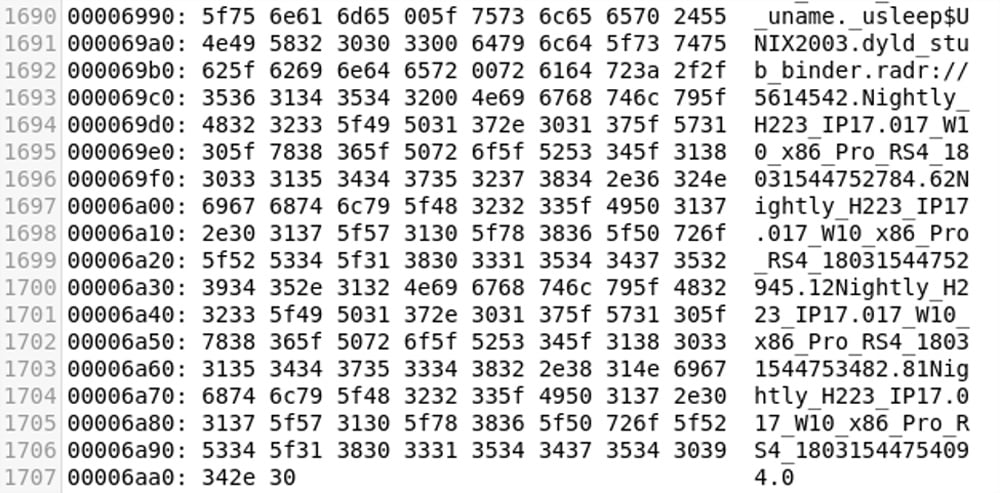

If we look at the Linkedit segment in the hex representation of the sample, we can see that some fuzzy strings have been appended at the end. These strings seem to contain a reference to different versions of Windows, and the end of these strings contains Unix timestamps. These actions change the hash of the sample, and consequently, avoid detection by Apple’s built-in protection.

Figure 4: Hex representation of a FlashBack sample

A similar analysis was performed by SentinelOne some time ago. They concluded that, while it is possible the malware authors are creating these minor variants so as to avoid detection and inflate the reach of Flashback, they could also be a result of a rogue automated script used, perhaps, by a security vendor.

Although our statistics show that Flashback was the most prevalent threat on the macOS platform in 2019, the numbers for that malware family might be inflated and deceiving. Whatever the case might be, ReversingLabs can protect your environment from these threats, while also allowing you to take a deeper look at the samples and find rather interesting information. For more information about our solutions, please check our homepage or contact us directly.

Get up to speed on key trends and learn expert insights with The State of Software Supply Chain Security 2024. Plus: Explore RL Spectra Assure for software supply chain security.